Dermatological Emergencies

Shilpi Khetarpal, MD

Anthony Fernandez, MD

Published: August 2014

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms

Definition

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome) is an idiosyncratic adverse drug reaction that affects the skin and various internal organs.

- Hallmarks of DRESS syndrome include a long latency period between initiation of the inciting medication and onset of the reaction (>2-3 weeks), fever, rash, and involvement of at least one internal organ system.

- Withdrawal of the inciting medication and systemic corticosteroids are mainstays of therapy.

Prevalence

DRESS syndrome, also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an idiosyncratic adverse drug reaction that can be fatal. DRESS is estimated to occur from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 10,000 drug exposures and typically occurs with the first exposure to a drug.1 Both genetic and acquired factors are thought to confer susceptibility to DRESS.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of DRESS is thought to be multifactorial and to include both immunologic and nonimmunologic factors. Proposed contributing factors include dysfunctional drug detoxification pathways which lead to accumulation of harmful metabolites and reactivation of herpes viruses, most notably HHV-6 and -7. Many medications have been reported to precipitate DRESS, but those classically associated include aromatic anticonvulsants, allopurinol, minocycline, sulfasalazine, and abacavir (Table 1).

Table 1: Common Causes of DRESS Syndrome

| Medication Class | Medications |

|---|---|

| Aromatic antiepileptics | Carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital |

| Other antiepileptics | Lamotrigine |

| Sulfonamide antibiotics | Trimethoprin-sulfamethoxasole |

| Other antibiotics | Minocycline, dapsone |

| Xanthine-oxidase inhibitors | Allopurinol |

| Aminosalicylates | Sulfasalazine |

| Other antirheumatics | Gold salts |

| Reverse transcriptase inhibitors | Abacavir |

DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

DRESS characteristically has a long latency period (>2-3weeks) between initiation of the inciting drug and onset of symptoms, which helps distinguish it from more typical simple drug reactions. The classic clinical presentation of DRESS includes the triad of fever, rash, and internal organ involvement. Fever and rash are the most common clinical manifestations, occurring in 85% and 75% of cases, respectively. Cutaneous lesions can vary in morphology, but central facial erythema and edema is relatively common and can serve as an important clue to the diagnosis (Fig. 1). Other common clinical findings include generalized lymphadenopathy, leukocytosis, abnormal liver function tests, and peripheral eosinophilia. Although peripheral eosinophilia is seen in more than half of affected patients and is part of the “DRESS” acronym, it is not required for the diagnosis.2 The most common visceral organ involved is the liver, and fulminant hepatitis is responsible for the majority of deaths due to DRESS. Importantly, cutaneous and visceral inflammation from DRESS may continue for weeks to months after drug withdrawal and has important implications when developing a treatment plan. The differential diagnosis includes various other adverse drug reactions and various systemic diseases based on the morphology of the skin lesions in any given patient.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DRESS can be challenging because of the variability in the morphology of cutaneous eruptions and internal organs involved from patient-to-patient. Several groups have proposed diagnostic criteria in the past. The regiSCAR diagnostic criteria include three requirements (hospitalization, acute rash, and suspicion of a drug-related reaction) PLUS at least three of the four following systemic features: (1) fever >38°C; (2) lymphadenopathy involving at least two sites; (3) involvement of at least one internal organ (e.g., liver, kidney, heart, etc.); and (4) hematologic abnormalities, including a lymphocyte count above or below the normal limits; an eosinophil count higher than laboratory limits; or a platelet count below laboratory limits.3

Treatment

Early and immediate withdrawal of the inciting medication is the most important intervention. As immune system dysfunction typically continues for several weeks after withdrawal of the inciting medication, systemic corticosteroids are often prescribed as first line therapy and tapered over a prolonged period.4 In refractory cases other immunosuppressants, including cyclosporine, have been used successfully. If DRESS is precipitated by an aromatic anticonvulsant it is important to transition the patient to a nonaromatic anticonvulsant, as cross reactivity among aromatic anticonvulsants can result in DRESS recurrence.2,4

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Definition

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are life-threatening mucocutaneous reactions, usually caused by a drug, characterized by diffuse keratinocyte apoptosis. The percent of affected body surface area (BSA) determines whether the reaction is described as SJS or TEN.

Prevalence

SJS and TEN represent opposite ends of a spectrum of the same rare, adverse immunologic reaction. The annual incidence is 1.2 to 6 per million for SJS and approximately 1 per million for TEN. The average mortality rate for SJS ranges from 1% to 5% but for TEN it is 25% to 35% and can be higher in elderly patients or those with high BSA involvement.5

Pathophysiology

SJS/TEN most often represents an adverse drug reaction, with over 100 drugs having been cited as causative agents in given individuals. The most common medications include allopurinol, NSAIDs, sulfonamide antibiotics, and anticonvulsants. Genetic factors that confer risk have been identified in some populations. Occasionally SJS/TEN may be precipitated by a viral illness. Immune dysregulation results in diffuse keratinocyte apoptosis that has been shown to involve FAS-FAS ligand interactions.5

Signs and Symptoms

SJS/TEN usually occurs 1 to 3 weeks after starting the causative drug. Initial manifestations are typically nonspecific and include fever, dysphagia, and a burning sensation of the eyes. These symptoms usually precede skin manifestations by several days. Skin involvement is often heralded by a sensation of diffuse skin pain. This is shortly followed by the appearance of dusky, atypical targetoid skin lesions, as well as mucosal erosions (Fig. 2). With progression the epidermis detaches from the underlying dermis, leading to bullae and epidermal sloughing (Fig. 3). Involvement of respiratory epithelium can lead to respiratory insufficiency, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and the need for mechanical ventilation. A variety of other organs can also be involved.5,6

Diagnosis

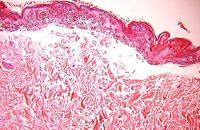

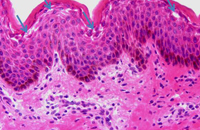

Diagnosis of SJS/TEN requires clinicopathologic correlation. The appropriate clinical findings include targetoid and atypical targetoid skin lesions and at least two mucosal surfaces involved (ocular, oral, genital, etc.).3,5 Nikolsky’s sign, which refers to epidermal detachment occurring with lateral pressure adjacent to bullae, is present and can be a clue to diagnosis. In patients with these appropriate clinical findings, a lesional skin biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other possible entities, including staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, generalized fixed drug eruption, and drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis.7 Lesional biopsies reveal full thickness epidermal necrosis with minimal dermal inflammation (Fig. 4).

Labeling as either SJS or TEN depends on the amount of epidermal detachment present: SJS implies <10% BSA epidermal detachment, SJS/TEN overlap is 10% to 30%, while TEN is >30% BSA epidermal detachment.

A thorough physical examination and routine blood work should be performed on all patients. Physical exam should direct investigations of other organ systems based on concern for involvement. SCORTEN is a validated severity of illness scoring tool that can be used to predict mortality from SJS/TEN (Table 2).8,9

Table 2: SCORETEN Criteria

| Criteria | Points = 0 | Points = 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤40 | >40 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | ≤120 | >120 |

| Underlying malignancy | Absent | Present |

| BSA involvement detached pidermis at time of scoring | ≤10% | >10% |

| Serum BUN (mg/dL) | ≤27 | >27 |

| Serum bicarbonate (mEq/L) | ≤20 | >20 |

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | ≤250 | >250 |

| *Total points are summed and correlate to risk of mortality as follows: | ||

| Total Points | Risk of Mortality |

|---|---|

| 0-1 | 3.2% |

| 2 | 12.1% |

| 3 | 35.3% |

| 4 | 58.3% |

| ≥5 | >90% |

BSA, body surface area; BUN, blood urea nitrogen

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment for SJS/TEN includes immediate discontinuation of the offending agent and supportive care. Supportive care involves maintenance of thermal regulation, fluid/volume replacement, maximizing protein nutrition, and meticulous wound care. As ocular sequelae are common, ophthalmology should be consulted to assess for ocular involvement and ensure optimal treatment in all diagnosed patients. Other supportive measures depend on which organs are involved. As apoptosis of keratinocytes is thought to be an immune-mediated event, use of steroid-sparing immunosuppressants makes theoretical sense but is a topic of significant controversy. Many tertiary care centers favor use of agents that include high dose intravenous immunoglobulins at a dose of 3 to 4 g/kg, systemic corticosteroids, or cyclosporine but studies definitively showing their efficacy are lacking.3,10

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Definition

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), also called Ritter’s disease, is a superficial skin blistering disorder caused by a localized infection with a staphylococcal strain that elaborates Staphylococcal exfoliative toxin (ET).

- Both children and adults can be affected, however it is much more common in children.

Prevalence

SSSS is rare, with an incidence estimated at approximately 0.56 cases per year per 1 million persons.11 Neonates and children are most commonly affected due to their decreased ability to renally clear the ETs and their lack of toxin-neutralizing antibodies. Adults are less commonly affected and tend to have significant comorbidities such as renal failure, immunosuppression, alcoholism, malignancy, or human immunodeficiency virus infection when they are affected.12 Although mortality is quite low in neonates in children, it can be as high as 50% in adults.

Pathophysiology

SSSS occurs when there is hematogenous dissemination of ETs produced by a localized infection with phage group II strains of S. aureus. The ETs produced by S. aureus are serine proteases that bind to and cleave desmoglein 1, a glycoprotein component of desmosomes in the epidermis. This leads to disruption of the granular layer in the epidermis thereby causing superficial blisters and exfoliation. Unlike in bullous impetigo where staphylococcal ETs are elaborated locally and only affect the infected site(s), the ETs in SSSS are spread hematogenously and therefore can affect the skin in a diffuse manner.

Signs and Symptoms

The primary infection begins focally in the conjunctiva, ear, urinary tract or skin. Initial manifestations include malaise and fever that then progress to diffuse erythroderma. Within 24 to 48 hours, flaccid bullae form in the flexures and around orifices.12, 13 Areas around the eyes and mouth are classically affected, and can have crinkled skin and desquamation.12, 13 Nikolsky’s sign is positive and, rarely, mucous membrane involvement can occur. Desquamation continues for 3 to 5 days then resolves without scarring (Fig. 5).

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of SSSS includes other serious diseases with prominent skin manifestations, including scarlet fever, SJS/TEN, and staph toxic shock syndrome. Whenever the possibility of SSSS is considered in the differential diagnosis, a lesional skin biopsy should be performed, as the histology can rule out other possible diseases (Fig. 6). The diagnosis of SSSS is based on the presence of three criteria: (1) appropriate clinical presentation with either erythroderma, skin desquamation, or bullae; (2) isolation of S. aureus strain that produces ET; (3) characteristic histopathology of intraepidermal cleavage at the granular layer.12, 13 Blood cultures are usually negative in children, but may be positive in adults.

Treatment

Patients should be hospitalized and antibiotics should be started immediately. Intravenous penicillinase-resistant penicillin is the treatment of choice to eradicate the infectious focus. Milder disease can be treated with an oral B-lactamase-resistant antibiotic (like dicloxacillin or cephalexin) for at least 7 days. Local therapy with compresses and barrier creams can be used as adjuncts. With proper treatment, SSSS typically resolves in 1 week. Decolonization of S. aureus carriers can decrease hospitalization times and recurrences.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Definition

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is an acute, endemic febrile illness caused by the bacteria Rickettsia rickettsii and is transmitted by a tick bite.

- The skin rash is the diagnostically critical clinical manifestation.

Prevalence

RMSF is the most common tickborne rickettsial disease in the United States, and occurs in all 48 contiguous states, except Vermont and Maine. Over 90% of cases occur between the months of April and September. Approximately 1,900 cases occur each year in the U.S.13,14

Pathophysiology

RMSF occurs after a tick bite, most frequently Dermacentor variabilis and less commonly Amblyomma americanum and Dermacentor andersoni. Rickettsia are injected into the bloodstream with tick saliva and then infect endothelial cells, causing increased vascular permeablity leading to edema, hypovolemia, and hypotension. Critical target organs in life-threatening infections are the lungs and brain.

Signs and Symptoms

After the tick bite, onset of symptoms ranges from 1 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days. The prodrome includes fever, chills, headache, and myalgias.13,14 The headache is often severe and can serve as a clue to the diagnosis. The skin manifestations begin 2 to 5 days after onset of fever as erythematous macules on the wrists, ankles, and forehead (i.e., distally). Lesions progress to purpura and spread in a distal-to-central manner, which is specific and diagnostic of RMSF in the appropriate clinical setting. Cutaneous necrosis can rarely occur. Fatality approaches 25% in untreated cases and 5% in treated cases.

Diagnosis

The most important diagnostic exam is the history and physical examination. Confirmation with indirect fluorescent antibody testing is currently the gold standard but cannot distinguish RMSF from other rickettsial infections. The most frequently used tests for diagnosis are indirect immunofluorescence and latex agglutination. Antibodies do not become positive until 2 to 3 weeks after the initial infection.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for RMSF is doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily. In children less than 9 years old or in pregnant females, the treatment of choice is chloramphenicol, 50 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours.14 Time between disease onset and initiation of treatment is one of the most important prognostic factors, as mortality increases significantly when treatment is delayed more than 5 days after onset. Therefore, treatment should be started empirically and never be delayed to wait for results of a confirmatory diagnostic test, underscoring the importance of recognizing the characteristic skin rash.

Sèzary Syndrome

Definition

- Sézary syndrome (SS) is an aggressive, leukemic variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

- It is characterized by the triad of erythroderma, lymphadenopathy, and Sézary cells (atypical neoplastic lymphocytes) in the bloodstream.

Prevalence

Primary cutaneous lymphomas are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and have an annual incidence of 1 in 100,000 persons. SS represents 3% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas and only occurs in adults.

Pathophysiology

SS represents the leukemic variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. There is debate about whether SS can arise via progression of typical T-cell lymphoma or whether it always represents a de novo phenomenon.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with SS classically present with the clinical triad of erythroderma, generalized lymphadenopathy and presence of neoplastic T-cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and blood (Sézary cells). Other common cutaneous features of SS include alopecia, palmoplantar keratoderma, ectropion and onychodystrophy (Fig. 7 and 8).15-17

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of erythroderma, including atopic dermatitis, pemphigus foliaceus, and psoriasis. When SS is a consideration, evaluation should include a complete physical exam, serologic testing (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase level, manual peripheral Sézary count, flow cytometry), and skin biopsy. The histopathologic features of SS include epidermotropism and a band-like infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes containing cerebriform nuclei. Immunohistochemical stains reveal the malignant cells have a phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, CD7–, and CD8–. EORTC diagnostic criteria for SS include (1) erythroderma, (2) demonstration of a dominant T-cell clone in peripheral blood by molecular methods PLUS one of the following: (a) absolute Sézary cell count ≥1,000 per mm3; (b) expanded CD4+ T-cell population resulting in a CD4:CD8 ratio >10; (c) expanded CD4+ T-cells with abnormal immunophenotype including loss of CD7 or CD26.16 Once a diagnosis is made CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed for staging purposes. The prognosis of SS is poor with the mean survival being 2 to 4 years and 5-year survival of 25%. If extracutaneous visceral involvement is identified the survival is less than 2.5 years.15-17 Most patients die of opportunistic infections from immunosuppression.

Treatment

The treatment of choice is extracorporeal photophoresis; either alone or in combination with other therapies. Other treatment options include low-dose chemotherapy, retinoids (bexarotene), denileukin diftitox, methotrexate, and interferon alpha. Skin directed therapies, including topical steroids and Psoralen-UVA, can be added as adjuvants.15-17 In the authors’ experience, the combination of extracorporeal photophoresis, bexarotene, and interferon alpha three times weekly is typically quite effective for a considerable amount of time in many patients.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Definition

- Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a life-threatening soft tissue infection that progresses rapidly to a life-threatening state.

- Nonspecific initial symptoms lead to misdiagnosis early, which significantly affects prognosis.

Prevalence

NF is a rare condition with approximately 1,000 cases reported each year in the US. Although uncommon, NF is associated with significant morbidity and a mortality rate between 20% and 60%.18,19

Pathophysiology

NF is caused by either traumatic/iatrogenic inoculation or hematogenous seeding of the fascia with pathogenic microorganisms. NF is classified into three types based on the organisms causing infection — type I: polymicrobial, type II: group A strep pyogenes, type III: marine vibrio. Risk factors for development include advancing age, diabetes, immunosuppression, peripheral vascular disease, surgery, and trauma.18,19 However, it can also occur in young, healthy people without underlying comorbidities.

Signs and Symptoms

NF is an infection of the superficial fascia and develops as organisms extend from the subcutaneous tissue and travel along fascial planes. It can affect the trunk, groin, head, or extremities. Early signs include fever, erythema and edema often mimicking cellulitis (the main entity in the differential diagnosis), leading to underestimation in the severity of the infection and delay in appropriate treatment (Fig. 9). As misdiagnosis and delay in appropriate treatment is considered the most important factor in fatal cases, knowledge of early clinical clues that help distinguish NF from cellulitis are important. Such clues include pain out of proportion to the physical exam, rapidly progressing erythema, associated myalgia, history of a puncture injury, and bullae formation. Late clues include crepitus, hypoesthesia of skin, prominent bullae and skin necrosis. Eventually septic shock with hypotension and multi-organ failure occurs.

Diagnosis

Rapid surgical debridement with tissue biopsy and cultures are the gold standard for diagnosis. However, deciding whether or not a patient should be taken to surgery for debridement can be quite difficult. In cases where the clinical diagnosis is unclear magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in guiding treatment, with specific NF findings including hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images at the deep fascia and within muscles.20 Additionally, the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score system has been developed for assessment of NF based on serologic factors such as C-reactive protein level, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and glucose levels.21

Treatment

Urgent and extensive surgical debridement of all necrotic and affected tissue is the mainstay of effective treatment. Occasionally, overwhelming necrosis necessitates limb amputation. Adjuvant medical treatment includes empiric broad spectrum antibiotics.18,19 Clindamycin is recommended if group A streptococcal bacteremia is suspected since it inhibits both M-protein and exotoxin production. Intravenous immunoglobulin infusions have been useful in some cases of severe group A streptococcal infection. Ampicillin and gentamicin cover aerobes, which are usually Gram-negative organisms.

Meningococcemia

Definition

- Meningococcemia is a systemic, febrile infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative encapsulated diplococcus Neisseria meningitides.

- Cutaneous lesions include petechiae and purpura that start on the trunk and extremities and can progress to purpura fulminans.

Prevalence

Approximately 20% of young adults are oropharyngeal N. meningitidis carriers, but only 1 in every 1,000 to 5,000 develops systemic disease.12, 22 Infection predominantly affects males and is most commonly seen in the winter and early spring. Children are most commonly affected because of their immature immune system; however, disease can rarely occur in adolescents and adults. Meningococcemia occurs worldwide, and is the leading cause of meningitis and septicemia in children and young adults in the U.S. The mortality rate has been estimated at 10% to 14%.

Pathophysiology

Infection occurs via transmission of respiratory droplets from carriers. Risk factors for infection include crowding (military barracks, college dormitories, etc.), complement deficiency, asplenia, and smoking. Once infected, N. meningitidis elaborates an endotoxin that triggers inflammatory processes which can lead to shock, multi-organ failure, and purpura fulminans. There are three N. meningitidis serotypes, A, B, and C. Serotype B is typically associated with sporadic cases of meningococcemia, whereas serotypes A and C are often associated with epidemic outbreaks.

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical presentation typically begins with fever, headache, and flu-like symptoms. Approximately 50% of patients will present with symptoms of frank meningitis, including headache, vomiting, psychomotor agitation, and nuchal rigidity. Myalgia can be intense and can be a clue to the diagnosis.

Cutaneous lesions typically are the first classic symptom of meningococcemia to appear. The key to meningococcemia is that it can progress extremely rapidly from flu-like symptoms to septic shock and a life-threatening situation. Therefore, recognizing the cutaneous lesions in distressed or incoherent patients can be life-saving by expediting appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Early cutaneous lesions are petechial and typically appear on the trunk, lower extremities, and areas of pressure such as the waistline.12, 22 Initially they can be few in number, but progression can lead to diffuse cutaneous involvement. With time, lesions develop a classic morphology of being angulated and having an erythematous border but “gun metal gray” interior appearance. Diffuse involvement of angulated lesions and purpura is referred to as purpura fulminans and is associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation and multi-organ failure. Differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic cutaneous lesions, fever, and headache include vasculitis, catastrophic antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, RMSF, and endocarditis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of meningococcemia is confirmed by detecting N. meningitidis in the bloodstream or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It is generally recommended that labs and blood cultures be drawn prior to initiating treatment to enhance probability of achieving an accurate diagnosis. However, as time is essential in this life-threatening condition, guidelines suggest that no more than 30 minutes elapse between consideration of the diagnosis and time to treatment. Additionally, treatment should not be delayed to wait for a lumbar puncture, despite the fact that, in general, CSF culture positivity > blood culture positivity > skin biopsy culture positivity. Skin biopsy shows endothelial damage with thrombi and neutrophils around the vessels; occasionally the organism can be seen in the thrombi.12, 22 Urine latex agglutination for N. meningitidis may be helpful for confirmation in patients who receive emergent treatment before a blood culture is obtained. RT-PCR, when available, can be performed on blood, skin, or CSF and can yield results faster than cultures and sensitivity is not affected by prior antibiotic administration

Treatment

Treatment consists of supportive care, respiratory isolation, and initiation of antibiotics. Currently, third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone) should be used as empiric treatment before culture results/sensitivities returned. A switch to penicillin-G 250,000 IU intravenously every 6 hours for 7 days is reasonable if the strain is susceptible. Adding vancomycin for resistant streptococcus is often done until results of cultures are known. Chloramphenicol and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are alternatives in penicillin-allergic patients. Rifampin is an alternative for children.12, 22 Importantly, household contacts, day-care contacts and exposed hospital personnel should receive prophylactic antibiotic treatment with rifampin 600 mg every 12 hours x 2 days or ciprofloxacin 500 mg x 1 day. Pregnant women should receive 250 mg ceftriaxone intramuscular. Treatment regimens are regularly updated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to account for changing Neisseria meningitidis strains and posted online. Vaccines protecting against several subtypes (including A and C) are available in U.S. and routinely given to patients at high risk for infection (college students in dorms and military recruits).

References

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online ahead of print May 17, 2011]. Am J Med 2011; 124:588–597. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.017.

- Walsh SA, Creamer D. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a clinical update and review of current thinking. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011; 36:6–11.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68:e1–e14.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68:e1–e9.

- Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs-the EuroSCAR-study [published online ahead of print September 6, 2007]. J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128:35–44. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701033.

- Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R, et al. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science 1998; 282:490–493.

- Thong BY. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: an Asia-Pacific perspective [published online ahead of print October 31, 2013]. Asia Pac Allergy 2013; 3:215–223. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.4.215.

- Guégan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigńe E, Roujeau JC, Revuz J. Performance of the SCORETEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126:272–276.

- Rajaratnam R, Mann C, Balasubramaniam P, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: retrospective analysis of 21 consecutive cases managed at a tertiary centre. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:853–862.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Analysis of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis using SCORETEN: the University of Miami experience. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139:39–43.

- Lamand V, Dauwalder O, Tristan A, et al. Epidemiological data of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in France from 1997 to 2007 and microbiological characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus associated strains [published online ahead of print October 19, 2012]. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:E514–E521. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12053.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Libia Cardozo Pereira A. Life-threatening eruptions due to infectious agents. J Clin Dermatol 2005; 23:148–156.

- Aronson PL, Florin TA. Pediatric dermatologic emergencies: a case-based approach for the pediatrician. Pediatric Ann 2009; 38:109–116.

- Dantas-Torres F. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7:724–732.

- Yamashita T, Fernandes Abbade LP, Alencar Marques ME, Alencar Marques S. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical review and update. An Bras Dermatol 2012; 87:817–828.

- Kubica AW, Davis MD, Weaver AL, Killiam JM, Pittelkow MR. Sézary syndrome: a study of 176 patients at Mayo Clinic [published online ahead of print May 27, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67:1189–1199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.043.

- Olsen EA, Rook AH, Zic J, et al. Sézary syndrome: immunopathogenesis, literature review of therapeutic options, and recommendations for therapy by the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC) [published online ahead of print December 9, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 64:352–404. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.037.

- Kihiczak GG, Schwartz RA, Kapila R. Necrotizing fasciitis: a deadly infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20:365–369.

- Lancerotto L, Tocco I, Salmaso R, Vindigni V, Bassetto F. Necrotizing fasciitis: classification, diagnosis, and management. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 72:560–566.

- Kim KT, Kim YJ, Won Lee J, et al. Can necrotizing infectious fasciitis be differentiated from nonnecrotizing infectious fasciitis with MR imaging [published online ahead of print March 15, 2011]? Radiology 2011; 259:816–824. doi:10.1148/radiol.11101164.

- Holland MJ. Application of the Laboratory Risk Indicator in Necrotising Fasciitis (LRINEC) score to patients in a tropical tertiary referral centre. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009; 37:588–592.

- Ferguson LE, Hormann MD, Parks DK, Yetman RJ. Neiserria meningitidis: presentation, treatment, and prevention. J Pediatr Health Care 2002; 16:119–124.