Hepatitis A

Talal Adhami

Ibrahim Hannouneh

Published: February 2014

Definition and Etiology

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a cause of acute liver inflammation or hepatitis. It can cause relapsing signs and symptoms but not a chronic infection. The virus is a 27-nm-diameter nonenveloped RNA virus. It belongs to the family Picornaviridae and the genus Hepatovirus. It has characteristics of the enteroviruses.1 Viral transmission occurs in a fecal-oral fashion. The genome is a positive-strand RNA, 7474 nucleotides long, 7.5 kb in length, that encodes a polyprotein with structural and nonstructural components. Viral replication and assembly occur in the hepatocyte cytoplasm of humans and nonhuman primates, the virus’ exclusive natural hosts. The virus is then secreted into the bile and serum.2

Prevalence

HAV is found throughout the world and is the most common cause of symptomatic acute hepatitis in the United States (annual incidence, 9.1/100,000), occurring largely as sporadic cases rather than epidemic. This figure has been declining since vaccines have become available and given to high-risk persons. The virus is more prevalent in areas with poor sanitary conditions. The most common source of hepatitis A is direct person-to-person exposure and, to a lesser extent, direct fecal contamination of food or water. Consumption of raw or partially cooked shellfish raised in contaminated waterways is an uncommon but possible source of hepatitis A.3Vertical transmission from mother to fetus and transmission from blood or blood products have been described on rare occasions. High-risk groups for acquiring HAV infection include travelers to developing nations, children in daycare centers, sewage workers, cleaning personnel, male homosexuals, intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs given plasma products, and persons in institutions. No identifiable source is found in 42% of all cases.4

In the United States, a region of relatively low hepatitis A endemicity, calculations based on surveillance data from 1989 indicated annual medical and work-loss costs of approximately US $200 million.5

Pathophysiology

HAV is not directly cytopathic to the hepatocyte. Injury to the liver is secondary to the host’s immune response. Replication of HAV occurs exclusively within the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted, HAV-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer cells mediate hepatocellular damage and destruction of infected hepatocytes. Interferon gamma appears to have a central role in promoting the clearance of infected hepatocytes.6,7

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical manifestations of HAV infection are widely variable, depending on the host response. They range from silent infection and spontaneous resolution to fulminant hepatic failure. The incubation period of HAV ranges from 15-49 days (mean, 25 days). The prodromal phase is characterized by nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, weakness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and, less commonly, fever. Headache, arthralgias, myalgias, rash, or diarrhea can follow. Jaundice begins within 1-2 weeks from the onset of the prodrome. It occurs in 70% of adults infected with HAV, with or without pruritus, and in a far smaller proportion of children. Mild hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and cervical lymphadenopathy are found in 85%, 15%, and 14% of infected patients, respectively.

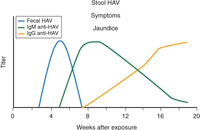

The host is infective from 14-21 days before the onset of jaundice to 7-8 days after jaundice has resolved.8 The host serum and saliva are not nearly as infectious as stool, and urine does not transmit the virus. Anti-HAV antibody (immunoglobulin M [IgM], followed by immunoglobulin G [IgG]) appears shortly before the onset of symptoms and rises to high titers 3-4 months after exposure. IgM-specific anti-HAV persists for 4-12 months, and IgG-specific anti-HAV persists for life (Figure 1). Extrahepatic manifestations are uncommon and include a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, arthritis, immune complex disease, toxic epidermal necrolysis, myocarditis, optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, polyneuritis, thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, and red cell aplasia.9

Diagnosis

Detecting IgM anti-HAV in the serum of a patient with the clinical and biochemical features of acute hepatitis usually confirms the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A.10

Figure 1 outlines the immune response to HAV infection. HAV antigen can be detected in the stool or body fluids, but there is no commercially available assay. Detecting viral RNA is highly specific but expensive and is rarely used to confirm the diagnosis. Liver biopsy is not indicated. Testing for anti-HAV IgG is not helpful in the diagnosis but is a means of assessing immunity to hepatitis A. When detected in the serum, this IgG remains positive for years.

Treatment and Prevention

Acute hepatitis A is usually a self-limited infection. Complete recovery is seen in most patients, and chronic disease does not occur. In rare cases, infection is complicated by fulminant disease, and fatalities occur. Treatment is mainly supportive. Attempts should be made to prevent transmission of the virus within the household and to close contacts. Boiling contaminated water for 20 minutes or exposing the virus to chlorine, formalin, or ultraviolet light reduces the risk of infection.11

A safe and effective hepatitis A vaccine is available and is recommended for patients at high risk of acquiring hepatitis A. Patients with chronic liver disease are more likely to develop severe or fulminant liver disease when infected with HAV and should be vaccinated. Hepatitis A vaccine is also recommended for patients with chronic immunodeficiency, those on dialysis, and those on chronic immunosuppressive therapies. Travelers from non-endemic to moderate or highly endemic areas should be vaccinated prior to their travel date, allowing time to develop protective antibodies. However, if travelling to a hepatitis A endemic area on short notice, protective immunoglobulin (IG) administration should be considered. Pre-exposure prophylaxis dose of 0.02 mL/kg IM confers protection for as long as 3 consecutive months. When administered within 2 weeks after an exposure to HAV (0.02 mL/kg IM), IG is 80%-90% effective in preventing hepatitis A. Efficacy is greatest when IG is administered early in the incubation period.

Two formulations of the HAV vaccine are available in the United States; both consist of inactivated hepatitis A antigen purified from cell culture. Havrix is recommended as 2 injections 6-12 months apart in an adult dose of 1440 U of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; 1.0 mL) and a pediatric dose (ages 2-18 years) of 720 U (0.5 mL). A dose of 360 U administered 3 times over a 6-month period is an acceptable regimen for children. Travelers to high-risk areas should receive the first dose of vaccine at least 4 weeks before anticipated exposure. Vaqta is recommended for administration as 2 injections at least 6 months apart in an adult dose of 50 U (1.0 mL) and a pediatric dose (2-17 years) of 25 U (0.5 mL). Protection lasts for approximately 15 years. None of the vaccines are licensed for children aged <1 year.

Hepatitis A vaccines have an excellent safety record, with serious complications in less than 0.1% of recipients. Vaccines used are highly immunogenic, and seroconversion rates after the HAV vaccine is given are higher than 90% but lower in patients with chronic liver disease (possibly as low as 50%). At least 50% of patients who are vaccinated after transplantation have titers below the protective level 2 years after receiving the vaccination. Patients with liver disease should therefore be vaccinated as early in their illness as possible. Follow-up testing for anti-HAV antibody and booster inoculations are not currently recommended. Pooled human immune globulin, 2 mL/kg in adults and 0.02 mL/kg in children, given intramuscularly, is recommended for postexposure prophylaxis. Efficacy is greatest (80%-90%) if the immunoglobulin is administered within the first 2 weeks after exposure. However, later administration attenuates the clinical expression of HAV infection.12

These recommendations for the prevention of hepatitis A are advocated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Outcomes

The course of hepatitis A infection is benign in most of those infected. It is occasionally severe, or fulminant, in adults, particularly in those with chronic liver disease. Jaundice usually resolves in less than 2 weeks, and full recovery usually occurs in 2 months. The illness occasionally persists for several weeks or months, but it never leads to a chronic infection, chronic hepatitis, or cirrhosis. A chronic relapsing hepatitis has been noted to last for as long as 1 year. Hepatitis A can cause a cholestatic hepatitis that usually responds to a short course of prednisolone, 30 mg daily. Pregnancy does not affect the severity or outcome of acute hepatitis A infection. In the rare case of fulminant hepatitis, patients should be evaluated early for possible liver transplantation.13

Summary

- Hepatitis A (HAV) is an RNA virus and the most common cause of symptomatic acute hepatitis in the United States. The main mode of transmission is fecal-oral, but consumption of raw shellfish and direct contact with contaminated blood can cause infection.

- HAV causes acute and relapsing hepatitis. It does not cause chronic hepatitis.

- Treatment is usually supportive, and hospitalization may be needed for severe cases. Liver transplantation is recommended in case of fulminant HAV hepatitis.

- There is a safe and effective vaccine to prevent HAV infection. It is recommended for patients at high risk of acquiring hepatitis A and for patients with chronic liver disease.

- Intramuscular human immune globulin is recommended for postexposure prophylaxis.

Suggested Readings

- Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 1999; 48(RR-12):1–37

References

- Feinstone SM. Hepatitis A: epidemiology and prevention. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8:300–305.

- Lemon SM, Jansen RW, Brown EA. Genetic, antigenic and biological differences between strains of hepatitis A virus. Vaccine 1992; 10(suppl 1):S40–S44.

- Koff RS. Preventing hepatitis A infections in travelers to endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995; 53:586–590.

- Bell BP, Shapiro CN, Alter MJ, et al. The diverse patterns of hepatitis A epidemiology in the United States: implications for vaccination strategies. J Infect Dis1998; 178:1579–1594.

- Weekly epidemiological record. World Health Organization website. www.who.int/docstore/wer/pdf/2000/wer7505.pdf. Published February 4, 2000. Accessed July 1, 2013.

- Fleischer B, Fleischer S, Maier K, et al. Clonal analysis of infiltrating T lymphocytes in liver tissue in viral hepatitis A. Immunology 1990; 69:14–19.

- Baba M, Hasegawa H, Nakayabu M, Fukai K, Suzuki S. Cytolytic activity of natural killer cells and lymphokine activated killer cells against hepatitis A virus infected fibroblasts. J Clin Lab Immunol 1993; 40:47–60.

- Tong MJ, el-Farra NS, Grew MI. Clinical manifestations of hepatitis A: recent experience in a community teaching hospital. J Infect Dis 1995; 171(suppl 1):S15–S18.

- Schiff ER. Atypical clinical manifestations of hepatitis A. Vaccine 1992; 10(suppl 1):S18–S20.

- Younossi ZM. Viral hepatitis guide for practicing physicians. Cleve Clin J Med 2000; 67(suppl 1):SI6–SI45.

- Koff RS. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccine 1992; 10(suppl 1):S15–S17.

- Winokur PL, Stapleton JT. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis for hepatitis A. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 14:580–586.

- Lemon SM. Type A viral hepatitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention. Clin Chem 1997; 43:1494–1499.