Alcoholic Liver Disease

Kyrsten D. Fairbanks

Published: November 2012

Definition

Liver disease related to alcohol consumption fits into 1 of 3 categories: fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, or cirrhosis (Table 1). Fatty liver, which occurs after acute alcohol ingestion, is generally reversible with abstinence and is not believed to predispose to any chronic form of liver disease if abstinence or moderation is maintained. Alcoholic hepatitis is an acute form of alcohol-induced liver injury that occurs with the consumption of a large quantity of alcohol over a prolonged period of time; it encompasses a spectrum of severity ranging from asymptomatic derangement of biochemistries to fulminant liver failure and death. Cirrhosis involves replacement of the normal hepatic parenchyma with extensive thick bands of fibrous tissue and regenerative nodules, which results in the clinical manifestations of portal hypertension and liver failure.

| Table 1. Forms of Alcoholic Liver Disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Fatty Liver | Alcoholic Hepatitis | Cirrhosis |

| Histologic specificity for alcoholic cause |

No | No | No |

| Prognosis | Excellent | Variable | Guarded |

| Reversible? | Yes | Variable | Generally no |

Prevalence

The prevalence of alcoholic liver disease is influenced by many factors, including genetic factors (eg, predilection to alcohol abuse, gender) and environmental factors (eg, availability of alcohol, social acceptability of alcohol use, concomitant hepatotoxic insults), and it is therefore difficult to define. In general, however, the risk of liver disease increases with the quantity and duration of alcohol intake.1,2 Although necessary, excessive alcohol use is not sufficient to promote alcoholic liver disease. Only 1 in 5 heavy drinkers develops alcoholic hepatitis, and 1 in 4 develops cirrhosis.3

Different alcoholic beverages contain varying quantities of alcohol (Table 2). Although fatty liver is a universal finding among heavy drinkers,3 up to 40% of those with modest alcohol intake (≤10 g/day) also exhibit fatty changes.1 Based on an autopsy series of men, a threshold daily alcohol intake of 40 g is necessary to produce pathologic changes of alcoholic hepatitis. Consumption of more than 80 g per day is associated with an increase in the severity of alcoholic hepatitis, but not in the overall prevalence.1 There is a clear dose-dependent relation between alcohol intake and the incidence of alcoholic cirrhosis. A daily intake of more than 60 g of alcohol in men and 20 g in women significantly increases the risk of cirrhosis. In addition, steady daily drinking, as compared with binge drinking, appears to be more harmful.3

| Table 2. Alcohol Content of Some Common Beverages | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drink | Amount (oz) | Absolute Alcohol (g) | |

| Beer | 12 | 12 | |

| Wine | 5 | 12 | |

| Liquor (80 proof) | 1.5 | 12 | |

Pathophysiology

The liver and, to a lesser extent, the gastrointestinal tract, are the main sites of alcohol metabolism. Within the liver there are 2 main pathways of alcohol metabolism: alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 2E1. Alcohol dehydrogenase is a hepatocyte cytosolic enzyme that converts alcohol to acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde subsequently is metabolized to acetate via the mitochondrial enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. CYP 2E1 also converts alcohol to acetaldehyde.4

Liver damage occurs through several interrelated pathways. Alcohol dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase cause the reduction of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) to NADH (reduced form of NAD). The altered ratio of NAD/NADH promotes fatty liver through the inhibition of gluconeogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. CYP 2E1, which is upregulated in chronic alcohol use, generates free radicals through the oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to NADP.4 Chronic alcohol exposure also activates hepatic macrophages, which then produce tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha).5 TNF-alpha induces mitochondria to increase the production of reactive oxygen species. This oxidative stress promotes hepatocyte necrosis and apoptosis, which is exaggerated in the alcoholic who is deficient in antioxidants such as glutathione and vitamin E. Free radicals initiate lipid peroxidation, which causes inflammation and fibrosis. Inflammation is also incited by acetaldehyde that, when bound covalently to cellular proteins, forms adducts that are antigenic.4

Natural History

With abstinence, morphologic changes of the fatty liver usually revert to normal. Although the short-term prognosis in patients with alcoholic steatosis is excellent, with longer follow-up it has been found that cirrhosis develops more commonly in alcohol abusers with fatty liver changes than in those with normal liver histology.6Morphologic features that predict progression to fibrosis, cirrhosis, or both include severe steatosis, giant mitochondria, and the presence of mixed macrovesicular-microvesicular steatosis.7

Historically, the 30-day mortality rate in patients with alcoholic hepatitis ranges from 0% to 50%.8 Clinical and laboratory features are powerful prognostic indicators for short-term mortality. Hepatic encephalopathy, derangement in renal function, hyperbilirubinemia, and prolonged prothrombin time are seen more often in patients who succumb to the illness than in those who survive.9 Both the discriminant function10 and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score11 can be used to predict short-term mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. The MELD score is calculated based on a patient’s prothrombin time, serum creatinine, and bilirubin; a calculator can be found on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Web site.12

The Lille model (LilleModel) is another prognostic scoring system that incorporates 6 reproducible clinical variables, including change in bilirubin in the first week during steroid therapy for severe alcoholic hepatitis. It is more accurate than the Child, Maddrey, Glasgow, or MELD scores in predicting death at 6 months in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.13 Long-term survival in patients with alcoholic hepatitis who discontinue alcohol is significantly longer than in those who continue to drink. Three-year survival approaches 90% in abstainers, whereas it is less than 70% in active drinkers.9 Duration of survival in both groups remains considerably below that of an age-matched population.

Cirrhosis has historically been considered an irreversible outcome following severe and prolonged liver damage. However, studies involving patients with liver disease from many distinct causes have shown convincingly that fibrosis and cirrhosis might have a component of reversibility.14 For patients with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis who undergo transplantation, survival is comparable to that of patients with other causes of liver disease; 5-year survival is approximately 70%.15

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with fatty liver typically are either asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms that do not suggest acute liver disease. Supporting features on physical examination include an enlarged and smooth, but rarely tender, liver. In the absence of a superimposed hepatic process, stigmata of chronic liver disease such as spider angiomas, ascites, or asterixis are likely absent.

Alcoholic hepatitis is a syndrome with a spectrum of severity, and therefore manifesting symptoms vary. Symptoms may be nonspecific and mild and include anorexia and weight loss, abdominal pain and distention, or nausea and vomiting. Alternatively, more severe and specific symptoms can include encephalopathy and hepatic failure. Physical findings include hepatomegaly, jaundice, ascites, spider angiomas, fever, and encephalopathy.16

Established alcoholic cirrhosis can manifest with decompensation without a preceding history of fatty liver or alcoholic hepatitis. Alternatively, alcoholic cirrhosis may be diagnosed concurrently with acute alcoholic hepatitis. The symptoms and signs of alcoholic cirrhosis do not help to differentiate it from other causes of cirrhosis. Patients may present with jaundice, pruritus, abnormal laboratory findings (eg, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy), or complications of portal hypertension, such as variceal bleeding, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy.

Diagnosis

Fatty liver is usually diagnosed in the asymptomatic patient who is undergoing evaluation for abnormal liver function tests; typically, aminotransferase levels are less than twice the upper limit of normal. No laboratory test is diagnostic of fatty liver. Characteristic ultrasonographic findings include a hyperechoic liver with or without hepatomegaly. Liver biopsy is rarely needed to diagnose fatty liver in the appropriate clinical setting, but it may be useful in excluding steatohepatitis or fibrosis.

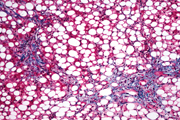

Typical histologic findings of fatty liver include fat accumulation in hepatocytes that is often macrovesicular, but it is occasionally microvesicular (Figure 1). The centrilobular region of the hepatic acinus is most commonly affected. In severe fatty liver, however, fat is distributed throughout the acinus.17 Fatty liver is not specific to alcohol ingestion; it is associated with obesity, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, malnutrition, and various medications. Attribution of fatty liver to alcohol use therefore requires a detailed and accurate patient history.

The diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis is also based on a thorough history, physical examination, and review of laboratory tests. Characteristically, the ratio of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is approximately 2:1 and the absolute aminotransferase level does not exceed ~300 U/L unless a superimposed hepatic insult exists, such as acetaminophen toxicity. Other common and nonspecific laboratory abnormalities include anemia and leukocytosis. Liver biopsy is occasionally necessary to secure the diagnosis.

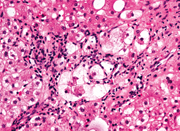

The classic histologic features of alcoholic hepatitis include inflammation and necrosis, which are most prominent in the centrilobular region of the hepatic acinus (Figure 2). Hepatocytes are classically ballooned, which causes compression of the sinusoid and reversible portal hypertension. The inflammatory cell infiltrate, located primarily in the sinusoids and close to necrotic hepatocytes, consists of polymorphonuclear cells and mononuclear cells. In addition to inflammation and necrosis, many patients with alcoholic hepatitis have fatty infiltration and Mallory bodies, which are intracellular perinuclear aggregations of intermediate filaments that are eosinophilic on hematoxylin-eosin staining. Neither fatty infiltration nor Mallory bodies are specific for alcoholic hepatitis or necessary for the diagnosis.16

The diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis rests on finding the classic signs and symptoms of end-stage liver disease in a patient with a history of significant alcohol intake. Patients tend to underreport their alcohol consumption, and discussions with family members and close friends can provide a more accurate estimation of alcohol intake.

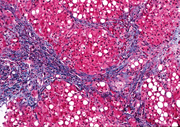

Patients can present with any or all complications of portal hypertension, including ascites, variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy. The histology of end-stage alcoholic cirrhosis, in the absence of acute alcoholic hepatitis, resembles that of advanced liver disease from many other causes, without any distinct pathologic findings (Figure 3).18

The overall clinical diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease, using a combination of physical findings, laboratory values, and clinical acumen, is relatively accurate (Table 3). However, liver biopsy can be justified in selected cases, especially when the diagnosis is in question. A clinical suspicion of alcoholic hepatitis may be inaccurate in up to 30% of patients.19 In addition to confirming the diagnosis, liver biopsy is also useful for ruling out other unsuspected causes of liver disease, better characterizing the extent of the damage, providing prognosis, and guiding therapeutic decision making.

| Table 3. Physical Examination and Laboratory Findings In Alcoholic Liver Disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Examination | |||

| Constitutional |

|

||

| Skin |

|

||

| Musculoskeletal |

|

||

| Genitourinary |

|

||

| Abdomen |

|

||

| Neurologic |

|

||

| Laboratory Findings | |||

| Liver synthetic function |

|

||

| Liver enzyme levels |

|

||

| Hematologic |

|

||

| Metabolic |

|

||

Treatment

The foundation of therapy for alcoholic liver disease is abstinence. Patients are often unable to achieve complete and durable alcohol abstinence without assistance, and referral to a chemical dependency team is appropriate. Hospitalization is indicated to expedite a diagnostic evaluation of patients with jaundice, encephalopathy, or ascites of unknown cause. In addition, patients with known alcoholic liver disease who present with renal failure, fever, inadequate oral intake to maintain hydration, or rapidly deteriorating liver function, as demonstrated by progressive encephalopathy or coagulopathy, should be hospitalized.

Nutritional Support

Supportive care for all patients includes adequate nutrition. Almost all patients with alcoholic hepatitis have some degree of malnutrition, but estimating the severity of malnutrition remains a challenge because sensitive and specific clinical or laboratory parameters are lacking. The nutritionist plays a valuable role in assessing the degree of malnutrition and guiding nutritional supplementation in malnourished alcoholic patients. The degree of malnutrition correlates directly with short-term (1-month) and long-term (1-year) mortality. At 1 year from the time of diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis, patients with mild malnutrition have a 14% mortality rate, compared with a 76% mortality rate in those with severe malnutrition.20 Attempts to correct protein-calorie malnutrition with supplemental oral or parenteral nutrition, or both, have met with mixed results. In general, enteral nutrition is preferable over parenteral supplementation, and protein should be supplied to provide positive nitrogen balance. Branched-chain amino acids are useful as a supplement to maintain positive nitrogen balance in patients who do not tolerate liberal protein intake because of the development of encephalopathy; however, the expense limits routine use in all alcoholic malnourished patients. Nutritional supplementation is generally associated with an improvement in liver test results, but only rarely with a mortality benefit.21 Refer to the most recent practice guidelines for a summary of recommendations for daily feeding in patients with alcoholic liver disease.19

Medical Treatment

The use of corticosteroids as specific therapy for alcoholic hepatitis has generated a good deal of interest. The rationale behind this approach is the possible role of the immune system in initiating and perpetuating hepatic damage. Three randomized, controlled trials investigating the use of corticosteroids (prednisolone 40 mg/day, or the equivalent methylprednisolone 28 mg/day, for 28 days) for patients with severe acute alcoholic hepatitis have been completed. The data suggest a significant decrease in short-term (30-day) mortality in patients randomized to prednisolone, but only those with more-severe liver dysfunction, as manifested by hepatic encephalopathy or a markedly abnormal discriminant function.10, 22, 23 The discriminant function predicts the risk of early mortality in patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis, and is calculated using the following formula:

(4.6 × [prothrombin time − control time]) + serum bilirubin (mg/dl)

with the prothrombin and control times in seconds.

Results from other randomized, controlled trials have been contradictory.24, 25Several meta-analyses have been conducted in an effort to overcome low statistical power in individual trials.26-28 Analyses by Mathurin and colleagues28 and Imperiale and McCul-lough26 support the use of corticosteroids in a select group of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis manifested by a discriminant function of more than 32, hepatic encephalopathy, or both. Christensen and Gluud27 found no effect of corticosteroids on mortality. Most recent trials of corticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis have excluded patients with certain coexisting conditions, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, active infection, diabetes, viral hepatitis, or acute pancreatitis, and therefore the applicability of these study findings is limited. Practice guidelines19 support the use of corticosteroids in patients in whom the diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis is certain.

Pentoxifylline, an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is also an inhibitor of TNF synthesis. Elevated TNF levels have been associated with higher mortality from alcoholic hepatitis.29 A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial investigated the effects of treatment with pentoxifylline on short-term survival and progression to the hepatorenal syndrome in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.30 Pentoxifylline-treated patients had a significant decrease in mortality (24% vs. 46%, P = .037). The survival advantage was primarily due to a decrease in the development of hepatorenal syndrome in pentoxifylline-treated patients (50% vs. 91.7%, P = .009).

Other therapies that have been investigated in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis but not found to be beneficial include propylthiouracil;31 infliximab;32 insulin and glucagon;33, 34 calcium channel blockers;35 antioxidants such as vitamin E,36 S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe),37 or silymarin,38 which is the active ingredient in milk thistle.

Liver Transplantation

Treatment of the patient with alcoholic cirrhosis mirrors the care of patients with any other type of cirrhosis, and includes prevention and management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal bleeding, encephalopathy, malnutrition, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Once advanced cirrhosis has occurred with evidence of decompensation (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), the patient should be referred to a transplantation center.

Acute alcoholic hepatitis is generally considered a contraindication to liver transplantation. For more than a decade, alcoholic cirrhosis has been the second leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States. Most transplantation centers currently require patients with a history of alcohol abuse to have documented abstinence of at least 6 months before undergoing transplantation. This requirement theoretically has a dual advantage of predicting long-term sobriety and allowing recovery of liver function from acute alcoholic hepatitis. This 6-month abstinence rule might not have much prognostic significance in predicting recidivism, however. Alcohol use of any quantity after transplantation for alcohol-related liver disease approaches 50% during the first 5 years, and abuse occurs in up to 15% of patients.39(Table 4) summarizes investigated treatments for alcoholic liver disease.

| Table 4. Treatments Investigated for Alcoholic Liver Disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Routine Use Recommended? | Potential Benefit | ||

| Abstinence | Yes | Survival | ||

| Nutritional support | Yes | Survival, laboratory | ||

| Corticosteroids | Yes | Survival | ||

| Pentoxifylline | Consider if DF ≥32 | Survival, less renal failure | ||

| Propylthiouracil | Consider (preliminary data) | No | ||

| Infliximab | No | No | ||

| Colchicine | No | No | ||

| Insulin, glucagon | No | No | ||

| Calcium channel blocker | No | No | ||

| Vitamin E | No | No | ||

| SAMe | No | No | ||

| Silymarin (milk thistle) | No | No | ||

| Liver transplantation | Consider (for decompensated cirrhosis) | Survival ~ 70% at 5 yr | ||

| DF, discriminant function. SAMe, S-adenosyl-L-methionine | ||||

Prevention and Screening

As emphasized in the most recent national practice guidelines,19 health care providers must be attentive for signs of covert alcohol abuse. Many patients do not openly disclose an accurate history of alcohol use. In addition, no physical examination finding or laboratory abnormality is specific for alcoholic liver disease. All patients should therefore be screened for alcohol abuse or dependency. Abuse is defined as harmful use of alcohol with the development of negative health and/or social consequences. Dependency is defined by physical tolerance and symptoms of withdrawal. The CAGE questionnaire (cutting down on drinking, annoyance at others’ concerns about drinking, feeling guilty about drinking, using alcohol as an eye opener in the morning) is the preferred screening tool, with more than 2 positive answers providing a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 95% for alcohol dependency.40

Conclusion

Clinicians should screen all patients for harmful patterns of alcohol use. All patients with alcohol-related liver disease should abstain from alcohol. For those with severe disease (ie, MDF ≥32 and/or hepatic encephalopathy), and no contraindications to their use, steroids should be considered. Liver transplantation remains an option for select patients with end-stage liver disease due to alcohol.

Summary

- All patients should be screened for alcoholic liver disease.

- Abstinence is the cornerstone of treatment of alcoholic liver disease.

- Alcoholic liver disease is a heterogeneous disease.

- The diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease requires a detailed patient history, with supportive laboratory and imaging studies.

- Liver biopsy may be useful to confirm the diagnosis, rule out other diseases, and prognosticate.

- Corticosteroids should be used in patients with a definite diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis, who have a discriminant function >32, hepatic encephalopathy, or both. Corticosteroids have not been evaluated in patients with renal failure, active infection, pancreatitis, or gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis should be evaluated for liver transplantation.

References

- Savolainen VT, Liesto K. Männikkö A, et al: Alcohol consumption and alcoholic liver disease: Evidence of a threshold level of effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1993;17(5):1112-1117.

- Lelbach WK: Cirrhosis in the alcoholic and its relation to the volume of alcohol abuse. Ann NY Acad Sci 1975;252:85-105.

- Grant BF, Dufour MC, Harford TC: Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 1988;8(1):12-25.

- Stewart S, Jones D, Day CP: Alcoholic liver disease: New insights into mechanisms and preventative strategies. Trends Mol Med 2001;7(9):408-413.

- Zhou Z, Wang L, Song Z, et al: A critical involvement of oxidative stress in acute alcohol-induced hepatic TNF-alpha production. Am J Pathol 2003;163(3):1137-1146.

- Sorensen TIA, Orholm M, Bentsen KD, et al: Prospective evaluation of alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver injury in men as predictors of development of cirrhosis. Lancet 1984;2(8397):241-244.

- Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, et al: Determinants of progression to cirrhosis and fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet 1995;356:987-990.

- Maddrey WC: Alcoholic hepatitis. In Williams R, Maddrey WC (eds): Liver. London: Butterworths, 1984, pp 226-241.

- Alexander JF, Lischner MW, Galambos JT: Natural history of alcoholic hepatitis II. Am J Gastroenterol 1971;56:515-521.

- Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, et al: Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1978;75:193-199.

- Sheth M, Riggs M, Patel T: Utility of the Mayo End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score in assessing prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterology 2002;2:2.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. MELD Calculator. OPTN: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Accessed November 6, 2012.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al: The Lille Model: A New Tool for Therapeutic Strategy in Patients with Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis Treated with Steroids. Hepatology 2007;45:1348-1354.

- Bonis PA, Friedman SL, Kaplan MM: Is liver fibrosis reversible? N Engl J Med 2001;344:452-454.

- Romano DR, Jimenez C, Rodriguez F, et al: Orthotopic liver transplantation in alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Transplant Proc 1999;31:2491-2493.

- Maddrey WC: Alcoholic hepatitis: Clinicopathologic features and therapy. Semin Liv Dis 1998;8(1):91-102.

- International Group: Alcoholic liver diseases: morphological manifestations. Lancet 1981;1(8222):707-711.

- Finlayson ND: Clinical features of alcoholic liver disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1993;7(3):627-640.

- O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ: Alcoholic Liver Disease. Hepatology 2010;51(1):307-328.

- Mendenhall CL, Tosch T, Weesner RE, et al: VA cooperative study on alcoholic hepatitis II: Prognostic significance of protein-calorie malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr1986;43:213-218.

- Schenker S, Halff GA: Nutritional therapy in alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 1993;13(2):196-209.

- Carithers RL, Herlong HF, Diehl AM, et al: Methylprednisolone therapy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Ann Intern Med 1989;110:685-690.

- Ramond MJ, Poynard T, Rueff B, et al: A randomized trial of prednisolone in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 1992;326:507-512.

- Depew W, Boyer T, Omata M, et al: Double-blind controlled trial of prednisolone therapy in patients with severe acute alcoholic hepatitis and spontaneous encephalopathy. Gastroenterol 1980;78(3):524-529.

- Theodossi A, Eddleston ALWF, Williams R: Controlled trial of methylprednisolone therapy in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Gut 1982; 23(1):75-79.

- Imperiale TF, McCullough AJ: Do corticosteroids reduce mortality from alcoholic hepatitis? Ann Intern Med 1990;113:299-307.

- Christensen E, Gluud C: Glucocorticoids are ineffective in alcoholic hepatitis: A meta-analysis adjusting for confounding variables. Gut 1995;37(1):113-118.

- Mathurin P, Mendenhall CL, Carithers RL, et al: Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): Individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatology 2002;36:480-487.

- Hallé P, Paré P, Kaptein E, et al: Double-blind, controlled trial of propylthiouracil in patients with severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1982;82:925-931.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, et al: Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1637-1648.

- Rambaldi A, Gluud C: Meta-analysis of propylthiouracil for alcoholic liver disease—a Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group Review. Liver 2001;21:398-404.

- Naveau S, Chollet-Martin S, Dharancy S, et al: A double-blind randomized controlled trial of infliximab associated with prednisolone in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2004;39:1390-1397.

- Bird G, Lau JYN, Koskinas J, et al: Insulin and glucagon infusion in acute alcoholic hepatitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Hepatology1991:14(6):1097-1101.

- Trinchet JC, Balkau B, Poupon RE, et al: Treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis by infusion of insulin and glucagon: A multicenter sequential trial. Hepatology1992;15(1):76-81.

- Bird GLA, Prach AT, McMahon AD, et al: Randomised controlled double-blind trial of the calcium channel antagonist amlodipine in the treatment of acute alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1998;28:194-198.

- Mezey E, Potter JJ, Rennie-Tankersley L, et al: A randomized placebo controlled trial of vitamin E for alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 2004;40(1):40-46.

- Rambaldi A, Gluud C: S-adenosyl-L-methionine for alcoholic liver diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;CD002235.

- Rambaldi A, Jacobs BP, Iaquinto G, et al: Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C liver diseases-a systematic cochrane hepato-biliary group review with meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2583-2591.

- Tome S, Lucey MR: Timing of liver transplantation in alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2003;39:302-307.

- Aertgeerts B. Buntinx F, Kester A: The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:30-39.